The field of behavioral economics is an interesting one. One of its central tenets is that there is a so called “behavior gap.”

This behavior gap describes how much less individual investors earn, on average when compared to the sum of their investments.

And the reason for this behavior gap is that in many ways we are hardwired to continually make wrong decisions. Our natural tendency is to be overconfident, and terrible market timers.

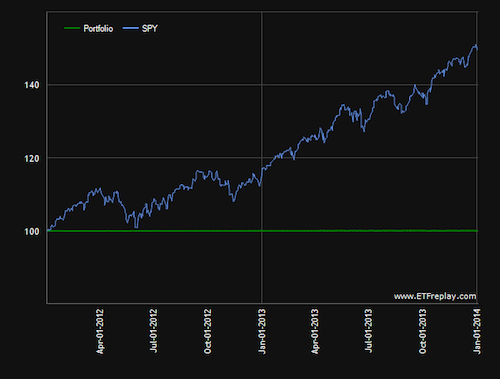

Imagine a simplified world where there are only two investment choices; short term treasuries and the S&P 500.

Now imagine you are an investor who has decided to split your allocation 50-50 between each of these two categories.

Let’s say you start in the year 2010.

Green = Short Term Treasuries. Blue = S&P.

Green = Short Term Treasuries. Blue = S&P.

It is now the beginning of 2014 and you have seen your S&P fund increase in value by 49% percent. Each month your treasuries have only lost value to inflation.

Every day you have checked the stock market and noted a volatile and explosive upward trend of the S&P 500.

What do you want to do now?

If you’re like me you’ll admit that what you’ll want to do is increase your percentage invested in the S&P 500.

You will want to double down on the investment that is giving you a positive reinforcement, and abandon the investment that is not performing well.

You will want to buy high and sell low.

Or imagine the converse. Imagine you invest in your 50-50 portfolio right at the height of the housing bubble in 2007.

Green = Short Term Treasuries. Blue = S&P.

Green = Short Term Treasuries. Blue = S&P.

Soon after investing, the bubble bursts and you watch in horror as your stock portfolio hemorrhages day after day, losing almost 50% of its value, even as your short term treasuries stay stone cold stable.

What will you want to do now? You will want to pull all of your money out of the stock market and put it all in safe short term treasuries.

You will want to sell low and buy high.

And logically, we can see that in both of these situations natural decision would’ve been exactly the wrong thing to do.

By buying when the market is rapidly climbing above normal levels of value you’re taking on more risk at exactly the time the market is most apt to collapse.

And by selling when the market has collapsed, you’re abandoning the market at exactly the time at which it is most likely to give you future outsized returns.

But here’s the thing: even if you know this logically, you will still want to do the wrong thing time and time again.

I consider myself a pretty rational person. But today I was overcome by the desire to sell my positions in small-cap stocks and move them into mid-cap stocks, because it is widely known (and has been widely reported) that small-cap stocks are currently very, very expensive when compared to the historic range of values.

(I was able to resist this urge, but if I had been more tired or stressed out, who knows?)

I think that the natural tendency when reading about the behavior gap, is to assume “yeah people are irrational, but I know about this tendency so I’m not going to fall into the trap.”

This is completely irrational!

Which brings me to prospect theory.

This is a concept that I read about last night in Daniel Kahneman’s wonderful book, Thinking, Fast And Slow.

Prospect theory looks at the conditions under which humans make decisions.

And since you’re (presumably) human, please read this scenario and answer it honestly:

Scenario 1:In addition to whatever you own, you’ve been given $1000. You are now asked to choose one of these options: a 50% chance to win $1000 or get $500 for sure.

Scenario 2: In addition to whatever you own, you have been given $2000. You’re now asked choose one of these options: A 50% chance to lose $1000 or lose $500 for sure.

Which did you choose in each scenario?

Most people will take the sure thing in question one and the gamble in question two.

Which is not exactly logical, right? In either scenario if you gamble and lose you end up with $1000 and if you gamble and win you end up with $2000. And in either scenario if you don’t take the gamble you end up with $1500.

So why do we make different choices?

The short answer is that although we like winning, we hate losing much more.

In addition we judge everything on a relative basis, so moving down to a level of $1500 gained feels very different from moving up to a level of $1500 gained.

Which kind of makes sense in an evolutionary sense. In the old days while roaming the plains it was adaptive to be more cautious in order to avoid terrible fates (that would prevent you from reproducing,) rather than being more aggressive and chasing bigger rewards at the risk of death.

Which is an important thing to remember when we are designing our portfolios.

On some level it is logical to allocate your portfolio very aggressively as a young person who is making money.

After all, over long time horizons high equity portfolios (up to 87 to 94% stocks) can be expected to perform the best, and paradoxically to have the least chance of running out of money.

But this completely ignores the imbalance of the experience of losing money when compared to the experience of winning money.

Winning money makes you pretty happy, but losing money makes you miserable.

And the biggest risk is in running away from investing when the going gets tough. This is a big part of the behavior gap.

According to this article, when you take into account all of the world’s markets the average worst 30 year performance in the stock market across all countries was almost -45%.

How many years into a 30 year experience of investing your money and losing progressively more of it could you sustain your enthusiasm and keep on investing?

I doubt many of us would make it past year 2.

Which I think is another example of why investors should match their bond percentages in their portfolios to their risk tolerance, as best they can.

The less risk tolerance you have, the more bonds you need.

And however much risk tolerance you think you have, prospect theory tells us that you probably have quite a bit less than that.

I also think this ends up being a very good argument for Roboadvisers like Betterment, that allow you to just “set it and forget it.”

I say Master Luke, perhaps you should leave investing to me?

I say Master Luke, perhaps you should leave investing to me?

Although you may think that you’re really really smart, and that you’ve got an excellent understanding of investing, (I’m guilty of this hubris) chances are the way you make decisions is pretty irrational.